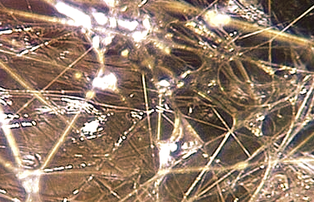

Fascia looks like cobwebs! Fascia looks like cobwebs! From a physiotherapist stand point, myofascial pain can sometimes be challenging to diagnose as the primary source of pain in a dog. Dogs are unable to describe to us exactly where their pain is and how it feels. As a canine physiotherapist, taking a good history from the owner and performing a thorough assessment on the dog is important in trying to distinguish myofascial pain from other sources of pain such as joint, ligament or nerve. So to understand pain that arises from myofascia (myo=muscle, and fascia=connective tissue) in a dog, first we need to look at exactly what this is and understand a bit more of the unique anatomy behind it. So what exactly is fascia? For most of you, you probably haven't heard of the term ' fascia' before. In the medical world, fascia had been long overlooked as being just a simple ‘ filler’ within the body, however we have learnt that its’ function is much more advanced than this in recent times. Fascia is an intricate network of enveloping connective tissue which spans throughout the body. It connects to organs, skin, muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones and holds everything together and aids in fluid movement. Microscopically, it actually looks like a stringy cobweb! There are three layers or types of fascia found throughout the body ; the superficial layer, the deep layer and the visceral layer and each is made up of collagen fibres that are packed closely together in bundles and are able to resist a great deal of force. The make up of these fibres also allow fascia to have a large flexibility component. The elastic property of fascia allows it to revert back to its’ normal form once compressional force has been lifted. Fascia is also considered to have a sensory component. It is rich in nerve endings which can sense pain and receptors which detect changes in posture/ position. This gives fascia the unique ability to transfer information to the brain for processing if a painful stimuli were detected or for monitoring or adjusting body position. More interestingly, fascia has a interoceptive property which senses ‘emotional awareness’ of the body. This system helps to sense feelings such as positive touch, warmth/ cold and sensing blood flow.

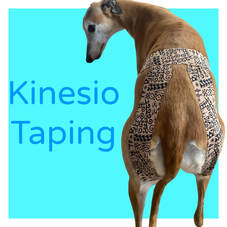

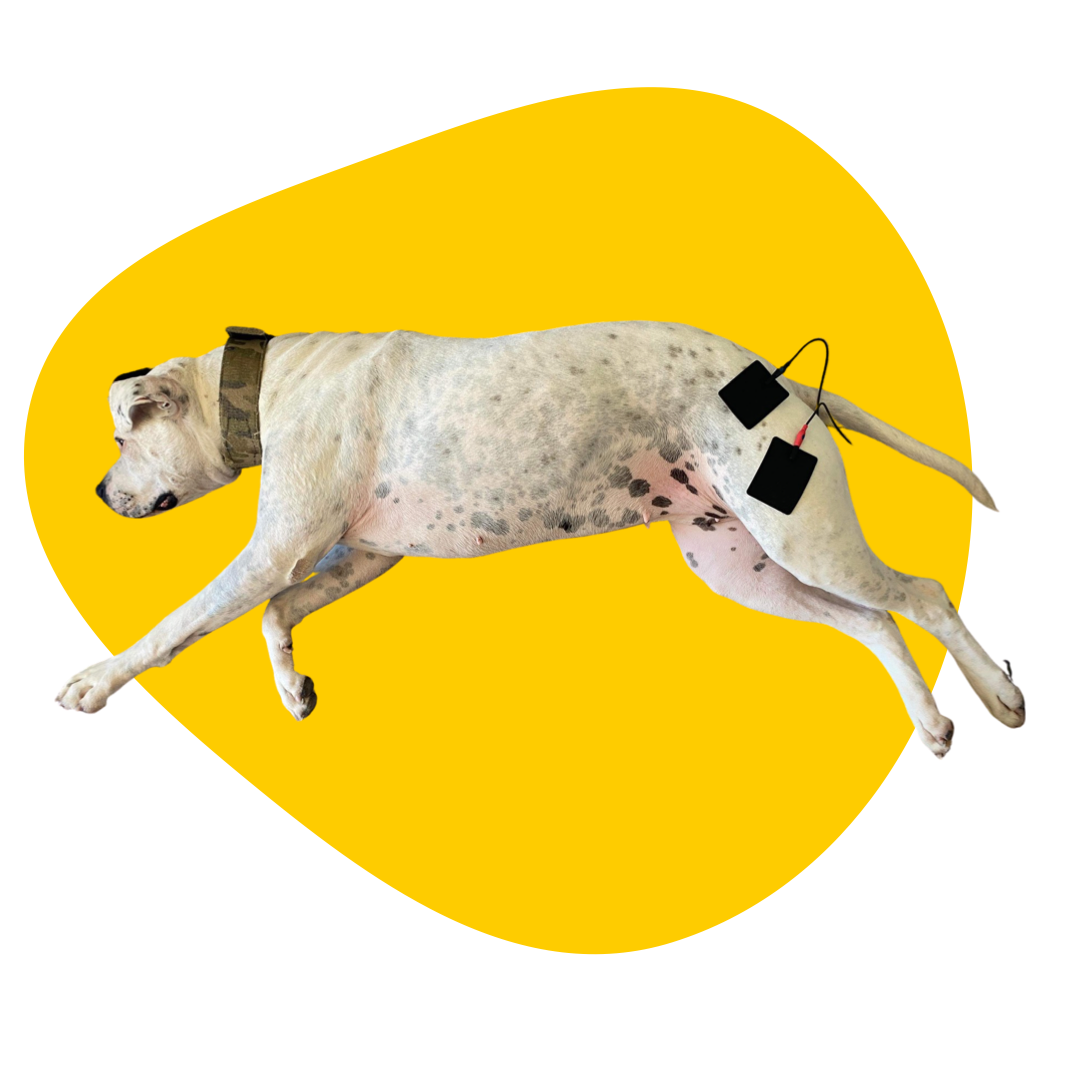

To date, research has been limited in this area. Myofascial pain has been defined as a ‘ regional pain syndrome caused by a dysfunction in muscle and surrounding fascia’ and is characterised usually by a myofascial trigger point. Which comes to my second point, what is a trigger point? A myofascial trigger point is a band of taught muscle which is painful to touch and can have the ability to refer pain to other areas of the body. As a dog is unable to tell us if pain is referring to other areas, then it is difficult for physiotherapists to make an informed decision if the trigger point, is in fact, the source of the dogs pain. Trigger points, once present, also reduce blood flow and therefore oxygen to the muscle and can lead to local inflammation and further contraction of the muscle. This restriction/contraction can lead to changes in posture and restrict the ‘gliding action’ of the fascia and muscle unit and can cause friction and lead to reduced fluid movement altogether. There are some signs and symptoms that dogs exhibit that help us to question whether or not myofascial pain may be contributing to pain and dysfunction in the canine. Some of these include hypersensitivity to touch, a ‘ twitch’ response when palpated, reduced range of movement and postural/behavioural changes. So now we know what myofascial pain is and how to identify it, now how to we treat it? You will be pleased to know that there are various treatment options available to help restore normal movement patterns and therefore reduce pain and dysfunction in dogs - woo hoo! Some hands on techniques that I love to use include releasing trigger points by means of sustained pressure to the taut band of muscle until a process called hysteresis occurs and the muscle relaxes and lengthens. Sustained stretch of the corresponding fascia will also help to lengthen out the myofascia however, both of these techniques are considered compressive in nature and don’t really aid in the mobility of the fluid between the layers which helps to hydrate the fascia. There are limited decompressive hands on treatment techniques for canines however cupping (used on humans) can help to lift the layers upward and therefore restore fluid mobility which is now starting to be used in the canine world! How exciting! Kinesio tape also has a ‘lifting’ and ‘decompressive’ role and electrotherapy techniques such as TENS, LLLT, ultrasound and dry needling also have can be used to treat myofascial pain syndrome. Besides treating the myofascial pain syndrome directly with hands on techniques, it is equally important to consider the other structures that have become weakened or overcompensated due to the myofascial restriction. Identifying these and implementing a structured strength and conditioning program will complement and aid in return to normal movement patterns.

Due to the complexity of fascia’s function and structure, I still believe more research is needed for us to fully understand and appreciate the implications it has on our canine patients, particularly when it becomes dysfunctional. |

AuthorJoanna Whitehead Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed